Authentication and authorization in a microservice architecture: Part 5 - implementing complex authorization using Oso Cloud

application architecture architecting securityContact me for information about consulting and training at your company.

The MEAP for Microservices Patterns 2nd edition is now available

This article is the fifth in a series of articles about authentication and authorization in a microservice architecture. The complete series is:

-

Overview of authentication and authorization in a microservice architecture

-

Implementing complex authorization using Oso Cloud - part 2

In part 3 - Implementing JWT-based authorization and part 4 - Implementing authorization using fetch and replicate, I described how a service that needs to authorize a request can obtain authorization data owned by other services using one of the following strategies:

-

Provide - the required authorization data is included in the access token

-

Fetch - the service retrieves the authorization data directly from another service, for example via its REST API

-

Replicate - the service maintains a local replica of the authorization data, synchronized using events (for example, the CQRS pattern)

While these strategies solve the problem of authorization using distributed data, implementing them can sometimes place an excessive burden on service developers. For example, the CQRS pattern requires writing additional code to publish and consume events, and maintain replicas. As the number of services and authorization relationships grows, the overall complexity and maintenance cost can increase rapidly.

In this article, I look at an alternative approach in which services delegate authorization decisions to a dedicated authorization service.

Motivation: why use an authorization service?

There are two main problems with each service implementing its own authorization logic.

The first problem is that passing authorization data between services can become costly and complex.

For example, the Customer Service must replicate its data into the Security System Service so that it can make authorization decisions.

Not only does this complicate both services, but each new service is potentially yet another place where this data must be shared and kept in sync.

The second problem is that implementing authorization logic inside services is difficult and error-prone. Authorization code typically consists of conditional logic and database queries that join multiple tables. The complexity of this code reflects the complexity of the underlying authorization rules. As those rules become more sophisticated, developing and maintaining the authorization logic becomes increasingly challenging.

Let’s look at how authorization-as-a-service can solve these problems.

An overview of authorization-as-a-Service

At first glance, authorization-as-a-service sounds similar to what OAuth 2.0 provides. However, OAuth 2.0 uses the term “authorization server” to describe a component that issues tokens containing scopes, not one that makes fine-grained authorization decisions. It is the resource server - such as the RealGuardIO application’s backend services - that uses those tokens to decide whether to allow access to an API endpoint. For example, in part 3 and part 4 of this series, I describe how those backend services make authorization decisions using data in the access token. OAuth does not determine whether a particular user can perform a specific action on a specific resource inside your system.

Modern authorization services fill this gap by working alongside the resource servers in your system. A resource server still validates access tokens, but instead of relying only on coarse-grained scopes, it can delegate fine-grained authorization decisions to the authorization service. The authorization service evaluates policy rules and data about users, roles, relationships, and resources to decide whether a specific action should be allowed. This approach provides policy-driven, fine-grained control over application behavior that is consistent across all services.

An authorization service has several key features:

-

A centralized component that manages authorization policies and evaluates authorize decisions across multiple applications or microservices.

-

A declarative policy language, such as Polar, Rego, or Cedar, for defining authorization rules instead of embedding them in application code.

-

A mechanism for services to supply facts — such as role assignments, relationships, and attributes — that describe the current state of the system.

-

A decision API that services call to check whether a user can perform an action on a resource, for example

isAllowed(user, action, resource). -

Consistent and explainable enforcement, so that all services rely on the same policies and data, making authorization decisions auditable and observable.

Several products implement this authorization-as-a-service model. Examples include Open Policy Agent (OPA), which uses the Rego policy language and is often embedded or self-hosted within a platform; AWS Verified Permissions, which uses the Cedar policy language and provides a managed, cloud-based service; and Oso Cloud, which uses the Polar policy language and offers both a hosted service and an on-premises option. In this article and the next, I focus on Oso Cloud.

A quick overview of Oso

Oso is an authorization-as-a-service platform that lets you define and enforce access control rules outside of application code. It stores authorization policies and data in a central service (Oso Cloud) and provides APIs for managing that data and checking permissions. Oso also supports a self-hosted mode for environments that cannot depend on a cloud service.

Oso policies are written in the Polar language. Polar is a declarative, logic-based language designed for fine-grained authorization that supports role-based access control (RBAC), relationship-based access control (ReBAC), and attribute-based access control (ABAC). Policies express who can perform which actions on which resources using concise, readable rules.

The following diagram shows a high-level view of the RealGuardIO application that uses Oso Cloud:

At a high level:

-

The application uploads its authorization policy to Oso Cloud

-

It sends facts that describe the current state of the system, such as role assignments and relationships

-

When a service needs to make an authorization decision, it calls Oso Cloud to check whether the user is allowed to perform an action on a resource

In addition, instead of sending facts to Oso, an application can also ask Oso to generate a SQL query fragment that enforces the same policy in its own database. This approach will be described in the next article.

A simple example: managing customer employees

To understand how Oso works, let’s start with a simple example from the RealGuardIO application.

The Customer Service implements a command called createCustomerEmployee(), which creates a new employee for a customer organization.

The authorization rule for this operation is straightforward:

A user can create an employee for a customer if and only if they have the

ADMINrole within that same customer.

Let’s first look at a traditional Java-based implementation of this policy. After that, we will look at the Oso version.

Implementing authorization checks in Java

In a traditional implementation, the service would query its database to retrieve the logged-in user’s roles with the specified customer and then check whether they have the required role.

This logic is usually written in Java and mixed in with other business logic, which makes it hard to understand, test, and maintain.

For example, here’s an excerpt of createCustomerEmployee() operation in the Customer Service:

public class CustomerService {

public CustomerEmployee createCustomerEmployee(Long customerId, PersonDetails personDetails) {

Customer customer = customerRepository.findRequiredById(customerId);

customerActionAuthorizer.verifyCanDo(customerId, RolesAndPermissions.CREATE_CUSTOMER_EMPLOYEE);

...

It calls the authorization logic with the specified customerID and the createCustomerEmployee permission.

Here’s the authorization logic:

public class LocalCustomerActionAuthorizer ... {

public void verifyCanDo(long customerId, String permission) {

Set<String> requiredRoles = RolesAndPermissions.rolesForPermission(permission);

String userId = userNameSupplier.getCurrentUserEmail();

Set<String> currentUserRolesAtCustomer = customerEmployeeRepository.findRolesInCustomer(customerId, userId);

if (Collections.disjoint(currentUserRolesAtCustomer, requiredRoles)) {

throw ...;

}

}

This logic is implemented imperatively in Java.

The verifyCanDo() method performs the following steps:

-

It finds the roles required to grant the permission

-

Finds the find the roles for the logged-in user at the customer

-

Throws an exception if the user doesn’t have the required role

Finally, here’s the finder method that the authorization logic uses to retrieve the user’s roles in the organization:

public interface CustomerEmployeeRepository

@Query("""

SELECT mr.name

FROM MemberRole mr, CustomerEmployee ce

WHERE mr.member.id = ce.memberId

AND mr.member.emailAddress.email = :employeeUserId

AND ce.customerId = :customerId

""")

Set<String> findRolesInCustomer(@Param("customerId") Long customerId,

@Param("employeeUserId") String employeeUserId);

The query joins multiple tables. As you can see, even for this simple authorization policy, the code is non-trivial. It mixes authorization logic with business logic and depends on repository queries and is potentially difficult to test or change as policies evolve.

Implementing authorization checks with Oso

With Oso, the authorization rules are written declaratively in the Polar language and evaluated by Oso Cloud. A simple policy that enforces this rule might look like this:

actor CustomerEmployee {}

resource Customer {

roles = ["COMPANY_ROLE_ADMIN", ...];

permissions = ["createCustomerEmployee", ...];

"createCustomerEmployee" if "COMPANY_ROLE_ADMIN";

}

This policy defines which customer employees can create other employees.

The line actor CustomerEmployee {} declares that CustomerEmployee is a type of actor (user) who acts on behalf of a customer organization.

The resource Customer { … } block defines the roles and permissions that apply to that organization.

Here, the COMPANY_ROLE_ADMIN role grants the createCustomerEmployee permission, meaning only admins within a customer organization can create new employees.

To make authorization decisions using this policy, Oso must know who holds which roles. This information is provided as facts. For example, the following fact tells Oso that Bob is an administrator for the customer Acme:

has_role(CustomerEmployee{"bob"}, "COMPANY_ROLE_ADMIN", Customer{"acme"});

This fact states that the actor Bob (a CustomerEmployee) has the COMPANY_ROLE_ADMIN role for the resource Customer{"acme"}.

Once Oso has the necessary facts — such as which employees belong to which customers and what roles they have — the application can delegate authorization decisions to Oso Cloud. For example, the application can query Oso with:

has_permission(CustomerEmployee{"bob"}, "createCustomerEmployee", Customer{"acme"})

This query asks: Can Bob create a customer employee for Acme?

Oso evaluates the query against the policy and facts.

Because Bob has the COMPANY_ROLE_ADMIN role for Acme, the policy rule "createCustomerEmployee" if "COMPANY_ROLE_ADMIN" applies, and Oso returns true.

This approach cleanly separates authorization logic from application code, making it easier to develop and maintain.

In the Oso-based implementation, the customerActionAuthorizer.verifyCanDo() method simply delegates the decision to Oso.

The only complication is that services such as the Customer Service must populate Oso with facts.

In the RealGuardIO application, this is done by publishing events that represent changes to roles and relationships.

This example is a straightforward, single-service authorization rule. RealGuardIO also has more complex scenarios where authorization decisions made by one service are based on roles, resources, and relationships owned by a different service. Let’s look at one of those next.

A more complicated example: managing security systems

The authorization policy for managing a security system — arming, disarming, and similar operations — is an example of a policy that spans multiple services.

The Security System Service must verify that the user is authorized to perform an operation using authorization data owned by the Customer Service.

As described previously, a customer employee can disarm a security system at a particular location if any of the following are true:

-

The employee is assigned the

SECURITY_SYSTEM_DISARMERrole in the security system’s location -

The employee is assigned the

SECURITY_SYSTEM_DISARMERrole in the company that owns the location -

The employee belongs to a team that is assigned the

SECURITY_SYSTEM_DISARMERrole in the security system’s location

Let’s first look at how this policy might be implemented using traditional Java code. After that, we will look at the Oso version.

Traditional Java implementation

As described in Part 4, there are two ways the Security System Service can obtain authorization data from the Customer Service.

-

Fetch - The

Security System Servicecalls theCustomer Servicedirectly, for example through a REST API, to look up the user’s roles for the relevant customer or location each time a request is authorized. This approach is simple but adds latency and runtime coupling between services. -

Replicate - The

Security System Servicemaintains a local copy of the necessary authorization data by subscribing to events published by theCustomer Service- the CARS pattern. This avoids runtime coupling but requires additional infrastructure to publish, consume, and update the replicated data.

Both approaches work, but as the authorization logic becomes more complex — involving multiple relationships such as teams, locations, and customers — they add significant implementation and maintenance overhead. Let’s now look at how Oso cloud instead.

Oso implementation

Let’s start by writing the Polar policy that captures the first two cases:

-

The employee is assigned the

SECURITY_SYSTEM_DISARMERrole in the security system’s location -

The employee is assigned the

SECURITY_SYSTEM_DISARMERrole in the company that owns the location

With these two cases, the action is performed on the SecuritySystem resource, but the authorization decision depends on roles assigned at related resources, Location or its Customer.

In Oso, the fact that permissions on one resource depend on roles defined on related resources can be expressed through the inheritance of roles based on relationships between resources.

Here’s the policy:

resource Customer {

roles = ["SECURITY_SYSTEM_DISARMER", ...];

...

}

resource Location {

relations = { customer: Customer };

roles = ["SECURITY_SYSTEM_DISARMER", ...];

"SECURITY_SYSTEM_DISARMER" if "SECURITY_SYSTEM_DISARMER" on "customer";

}

resource SecuritySystem {

relations = { location: Location };

permissions = ["disarm", ...];

"disarm" if "SECURITY_SYSTEM_DISARMER" on "location";

}

These policy elements define how the SECURITY_SYSTEM_DISARMER role and the disarm permission are inherited through relationships between resources:

-

The

Customerresource defines the roleSECURITY_SYSTEM_DISARMER. -

The

Locationresource, which is related to aCustomerthrough thecustomerrelation, also defines the same role. -

The rule

"SECURITY_SYSTEM_DISARMER" if "SECURITY_SYSTEM_DISARMER" on "customer";means that anyone who has theSECURITY_SYSTEM_DISARMERrole on aCustomerautomatically has that role on all of itsLocations. -

The

SecuritySystemresource defines alocationrelation and the rule"disarm" if "SECURITY_SYSTEM_DISARMER" on "location";, which grants thedisarmpermission to anyone who has that role at the security system’sLocation.

Together, these rules implement the intended behavior.

Next, let’s extend this policy to handle the third case where a CustomerEmployee belongs to a Team that has been assigned the SECURITY_SYSTEM_DISARMER role on a Location.

This case differs from the other two because it involves a relationship between actors and resources, not just between resources.

The first step is to represent teams and their members.

The Team resource defines a members relation that links each team to one or more CustomerEmployees:

resource Team {

relations = { members: CustomerEmployee };

}

This establishes the concept of team membership. With this in place, we can write a Polar rule that defines how a customer employee inherits a role from a team they belong to:

has_role(u: CustomerEmployee, role: String, loc: Location) if

team matches Team and

has_relation(team, "members", u) and

has_role(team, role, loc);

This rule says that a CustomerEmployee u has a given role on a Location loc if there exists a Team that includes the user (has_relation(team, "members", u)) and that same team has the role on the Location (has_role(team, role, loc)).

In other words, roles assigned to teams are inherited by all their members.

Polar resource blocks are shorthand for explicit rules

I was surprised when I first figured out how to implement teams.

The has_role(…) if … rule looks quite different from the resource definitions.

But I then learned that Resource definitions are actually a shorthand for a set of more explicit Polar rules.

For example, the Location resource:

resource Location {

relations = { customer: Customer };

roles = ["SECURITY_SYSTEM_DISARMER", ...];

"SECURITY_SYSTEM_DISARMER" if "SECURITY_SYSTEM_DISARMER" on "customer";

}

is shorthand for the following more explicit Polar rule:

has_role(u, "SECURITY_SYSTEM_DISARMER", loc: Location) if

has_relation(loc, "customer", cust) and

has_role(u, "SECURITY_SYSTEM_DISARMER", cust);

And, the SecuritySystem resource:

resource SecuritySystem {

relations = { location: Location };

permissions = ["disarm", ...];

"disarm" if "SECURITY_SYSTEM_DISARMER" on "location";

}

is shorthand for the following more explicit Polar rule:

has_permission(u, "disarm", ss: SecuritySystem) if

has_relation(ss, "location", loc) and

has_role(u, "SECURITY_SYSTEM_DISARMER", loc);

As you can see, an Oso policy is a set of rules such as has_role(…) if … and has_permission(…) if ….

The body of each rule defines the conditions that must be true for the rule to succeed.

These conditions are usually expressed as other rules, comparisons, or function calls that the policy engine evaluates recursively.

In contrast, facts specify statements like has_role(…) and has_relation(…) without an if clause.

Facts are unconditional truths that represent the current state of the world, while rules describe how to derive new truths from those facts.

Let’s look at how Oso uses these rules and facts to determine whether a user has permission to perform an action.

How Oso evaluates queries

Oso’s policy evaluation is driven by unification, a concept from logic programming languages such as Prolog.

Unification is the process of finding variable bindings that make different logical expressions identical.

When a query such as has_permission(CustomerEmployee{"alice"}, "disarm", SecuritySystem{"ss1"}) is evaluated, Oso tries to unify it with the patterns defined in the policy’s rules, like has_permission(u, "disarm", ss: SecuritySystem) if ….

If the query matches the head of the rule, Oso substitutes concrete values (for example, u = CustomerEmployee{"alice"}, ss = SecuritySystem{"ss1"}) into the rule and then recursively evaluates the conditions in the rule body: has_relation(ss, "location", loc) and has_role(u, "SECURITY_SYSTEM_DISARMER", loc).

Each recursive step involves further unification against other rules or facts.

For example, has_relation(SecuritySystem{"ss1"}, "location", loc) would match against the fact that specifies the security system’s location, such as has_relation(SecuritySystem{"ss1"}, "location", Location{"loc1"}).

Oso then needs to prove has_role(CustomerEmployee{"alice"}, "SECURITY_SYSTEM_DISARMER", Location{"loc1"}).

This could match against a fact if the user has been assigned a role at a location, or it’s resolved through the rules for role inheritance from teams or customers.

Through this chain of unifications, Oso builds a logical proof that the permission is granted or determines that no such proof exists.

Now that we’ve seen how Oso evaluates queries, let’s look at how Oso Cloud is integrated into the RealGuardIO application. This will show how facts flow from the backend services to Oso to support authorization decisions.

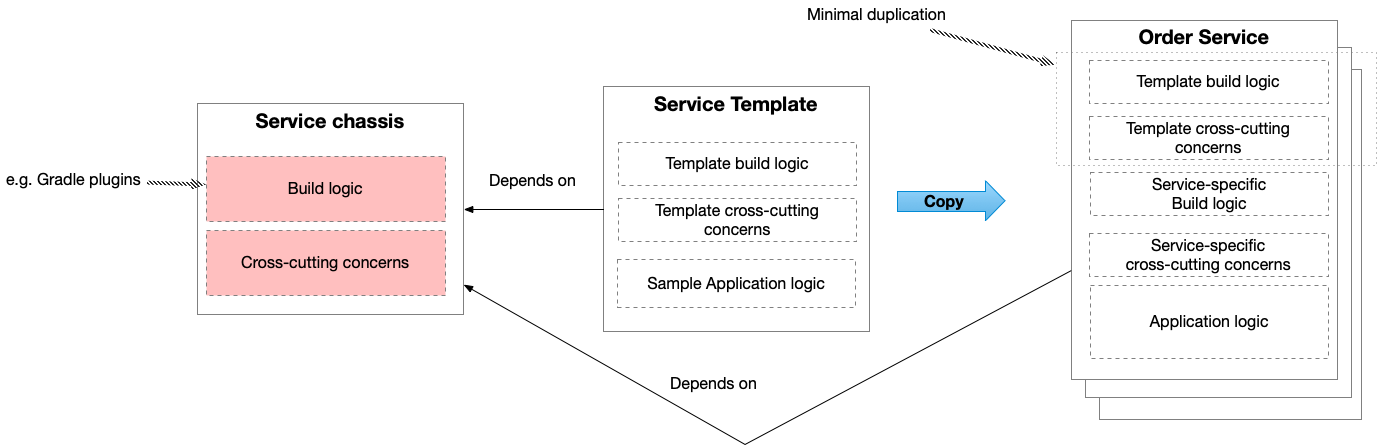

Integrating Oso Cloud into the RealGuardIO application

The RealGuardIO backend services interact with Oso Cloud in two ways. First, services that own data corresponding to the facts used by the policy must populate Oso. Second, services that need to authorize requests call Oso to make authorization decisions. The following diagram shows the architecture:

Let’s first explore how Oso is populated with facts. After that, we’ll look at how authorization decisions are made.

Responsibilities of data-owning services

Oso Cloud is integrated into the RealGuardIO application using a variation of the CQRS pattern.

Services that own data corresponding to facts — such as the Customer Service — publish events.

An Oso Integration Service subscribes to those events and sends the facts to Oso.

For example, the assignLocationRole() operation, which assigns a CustomerEmployee a role at a Location, results in the publication of a CustomerEmployeeAssignedLocationRole event:

-

The

Customer Servicehandles the request by assigning theCustomerEmployeethe specified role and location. -

The

Customer Servicepublishes aCustomerEmployeeAssignedLocationRoleevent. -

The

Oso Integration Servicehandles the event by creating the facthas_role(CustomerEmployee{"mary"}, "SECURITY_SYSTEM_DISARMER", Location{"loc3"})in Oso.

Here, for example, is an except:

public class CustomerService {

private final CustomerEventPublisher customerEventPublisher;

@Transactional

public CustomerEmployeeLocationRole assignLocationRole(Long customerId, Long customerEmployeeId, Long locationId, String roleName) {

...

customerEventPublisher.publish(customer,

new CustomerEmployeeAssignedLocationRole(userName, locationId, roleName));

...

The CustomerEventPublisher is implemented using the Eventuate Platform, which supports the Transactional Outbox pattern.

This pattern ensures that assigning the role and publishing the corresponding event occur atomically as part of a single database transaction.

Without it, there would be a risk of inconsistencies between the Customer Service and Oso if an event were published without the database update, or vice versa.

The Oso Integration Service populates Oso with facts using the Oso Java SDK, which invokes the Oso REST API.

For example, this call to the Oso API creates a fact stating that a CustomerEmployee has the COMPANY_ROLE_ADMIN at a Company:

import com.osohq.oso_cloud.Oso;

Oso oso = new Oso(apiKey, URI.create(osoUrl);

oso.insert(new Fact(

"has_role",

new Value("CustomerEmployee", userId),

new Value("COMPANY_ROLE_ADMIN"),

new Value("Customer", customerId)

));

Let’s now look at how services make authorization decisions using Oso.

Responsibilities of services that authorize requests

Services that need to authorize requests delegate authorization decisions to Oso Cloud rather than implementing them locally. When a request arrives, the service calls Oso to check whether the user is allowed to perform the requested action on the specified resource. This approach replaces complex, hand-coded authorization logic with a simple API call.

For example, the Customer Service and Security System Service use the Oso Java SDK to call the POST /authorize REST endpoint, which is Oso’s equivalent of isAllowed(user, action, resource).

Both services pass the identity of the logged-in user as the actor.

The Customer Service passes the customerId as the resource, while the Security System Service passes the securitySystemId.

Here, for example, is how the Security System Service can check whether a user is authorized to disarm a security system:

boolean canDisarm = oso.authorize(

new Value("CustomerEmployee", userId),

"disarm",

new Value("SecuritySystem", securitySystemId)

)

Show me the code

The RealGuardIO application (work-in-progress) can be found in the following GitHub repository.

Acknowledgements

Thanks to Meghan Gill and Hazal Mestci for reviewing this article and providing valuable feedback.

Summary

-

An authorization service manages authorization policies, which are written in a declarative policy language, and provides an API for making authorization decisions.

-

To make those decisions, services must provide the authorization service with facts — such as role assignments, relationships, and attributes — that describe the current state of the system.

-

Oso is an authorization-as-a-service platform available as a cloud service or as a self-hosted deployment.

-

Oso policies are written in Polar, a declarative, logic-based language for expressing fine-grained authorization rules.

-

Oso makes authorization decisions using facts stored in Oso Cloud, facts stored in the application’s database, or a combination of both.

-

Using an authorization service such as Oso simplifies the implementation of authorization within each microservice, since the services no longer need to contain complex, hand-coded logic — such as Java conditional logic and SQL queries that do multi-table database joins.

-

In the RealGuardIO application, services such as the

Customer Service— which own data corresponding to facts — update Oso using the event-based CQRS pattern

What’s next?

In this article, we saw how services can delegate authorization decisions to Oso Cloud. We explored how services that own authorization data publish events that populate Oso cloud with facts. In the next article, we’ll look at another way to use Oso: generating database query fragments that enforce authorization rules directly within a service’s data access logic. This approach enables a service to execute bulk queries efficiently while maintaining the same declarative, centralized policy model.

Need help with accelerating software delivery?

I’m available to help your organization improve agility and competitiveness through better software architecture: training workshops, architecture reviews, etc.

Premium content now available for paid subscribers at

Premium content now available for paid subscribers at