How modular can your monolith go? Part 4 - physical design principles for faster builds

architecting modular monolithContact me for information about consulting and training at your company.

The MEAP for Microservices Patterns 2nd edition is now available

This article is the fourth in a series of articles about modular monoliths. The other articles are:

- Part 1 - the basics

- Part 2 - a first look at how subdomains collaborate

- Part 3 - encapsulating a subdomain behind a facade

- Part 5 - decoupling domains with the Observer pattern

- Part 6 - transaction management for commands

- Part 7 - no such thing as a modular monolith?

In the previous article, I described how using a facade to encapsulate each subdomain’s API can reduce design-time coupling and improve testability.

In the example application, the CustomerService facade insulates the orders domain from changes to the customers domain.

Minimizing design-time coupling is not the only concern, however.

We also need to minimize build times, especially test execution times.

In this article, I’ll describe how to use physical design principles to reduce build-time coupling between modules.

A fast deployment pipeline is essential for developer productivity

In order to deliver software rapidly, frequently and reliably, it’s essential to have a fast deployment pipeline. Ideally, a deployment pipeline should take no more than 15 minutes to build, test and begin deployment to production. This will guarantee that a developer will get prompt feedback about their changes. It also ensures that the deployment pipeline will not become an obstacle to continuous delivery, where developers are committing at least daily to trunk.

The challenge with a modular monolith - unlike a microservice architecture - is that you have a single codebase, which could be very large and potentially take a very long time to build and test. Consequently, it’s important to minimize the build-time coupling between the monolith’s modules. The degree of build-time coupling between modules A and B is the likelihood of that a change to A (which requires A to be recompiled and tested), also requires B to be recompiled and/or retested. Ideally, a change to a given module should only require that module to be recompiled and retested, since that will be the fastest possible build. The worst case would be a change to a given module that requires all modules to be recompiled and retested.

Test execution time is often more longer than the compilation time

The build time is the sum of the compilation time and the test execution time. Quite often test execution time is far longer than compilation time. Unit tests are typically very fast since they are entirely in memory. But other types of tests (see the test pyramid) are usually much slower, since they often involve heavyweight technologies, such as networks, databases, and containers.

Modern build tools try to be lazy but …

Modern build tools, such as Maven and Gradle, try to minimize the amount of work that they need to do. For example, a task is skipped if its inputs and outputs are unchanged. A task might only reprocess those input files that have actually changed. Gradle can even avoid recompiling clients of a class whose internal details have changed. Unfortunately, however, build tools typically run all of a module’s tests if any class in either the module or any of its dependencies has changed.

This behavior means that in the example application, a change to the CustomerService class in the customers domain will cause all tests in the orders domain to be re-run even if the change does not require recompilation of the orders domain.

As a result, the build time is longer than it needs to be.

In a real application, a change to customers domain might trigger the retesting of numerous transitive dependencies, which could take a very long time.

The solution is to organize the code by applying some physical design principles.

Apply physical design principles to reduce build-time coupling

As I mentioned a while ago, one of my favorite books from the 1990s is Large Scale C++ Design by John Lakos. While much of the book is C++-specific (not my most favorite language), it makes an important contribution: physical vs. logical software design. Logical software design is the main focus of software design techniques, such as object-oriented design and Domain-Driven Design: naming, assignment of responsibilities to classes and packages, class hierarchies, encapsulation, loose (design-time) coupling, cohesion etc. Ideas that are essential if we want our software to be understandable and maintainable.

Lakos argues, however, that for large scale software, logical design is insufficient. We also must consider the physical design of the software, which is the structure of the application’s physical entities, such as source files, Gradle projects/Maven modules - the file system artifacts consumed by the build tools. That’s because physical design determines, among other things, build-time coupling between modules. Lakos describes insulation techniques (analogous to encapsulation techniques for reducing design-time coupling) that can be used to reduce compile-time coupling.

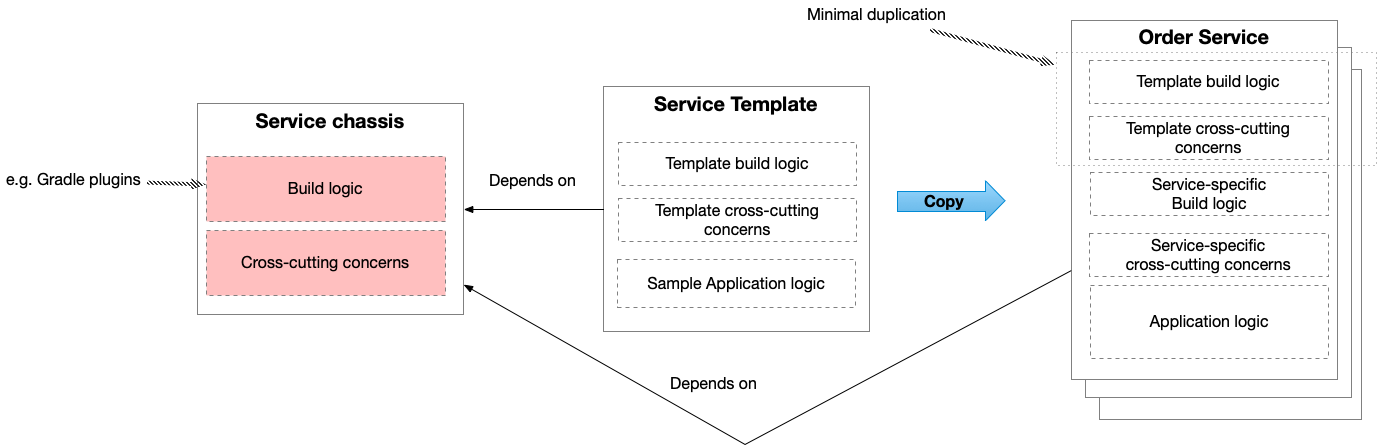

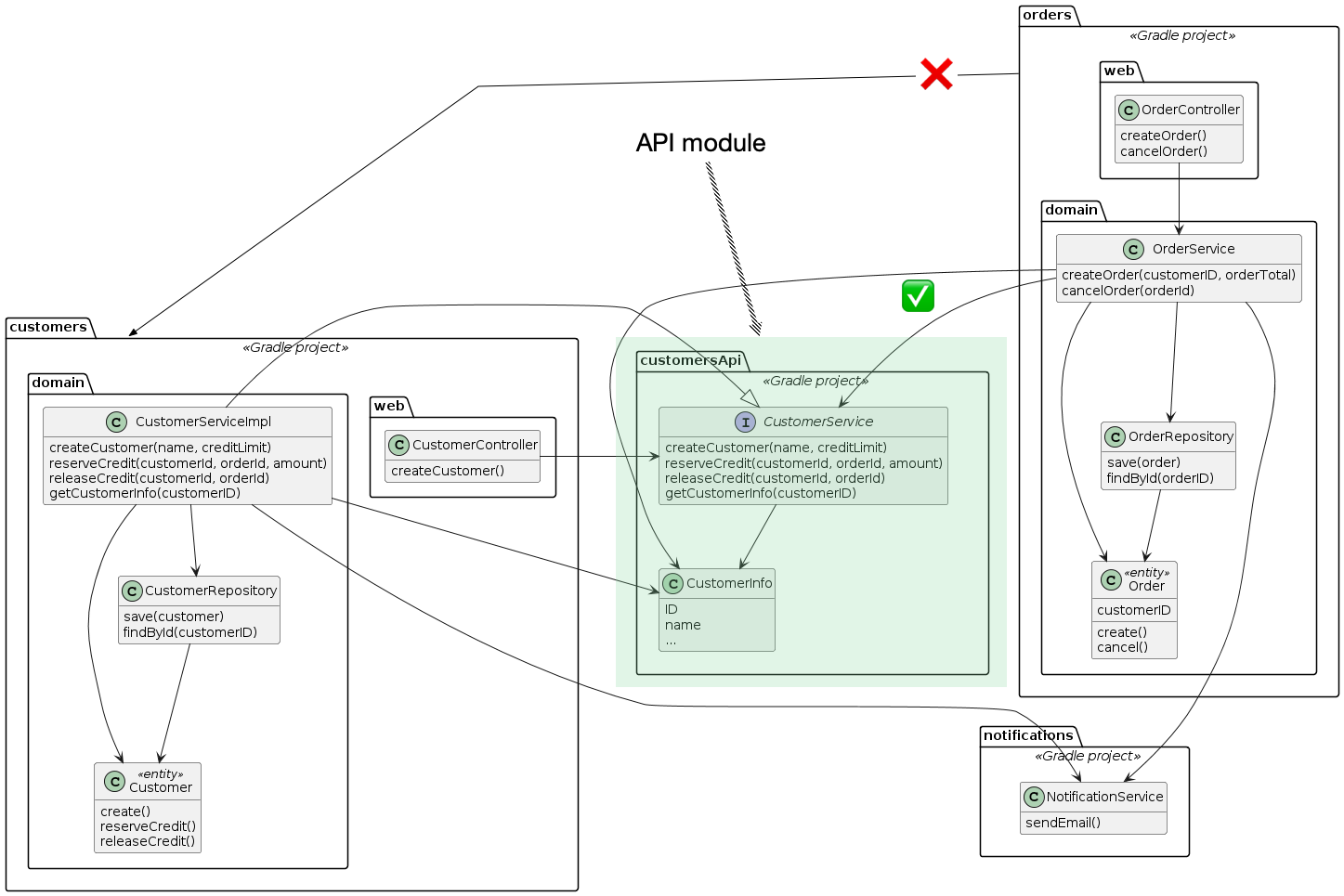

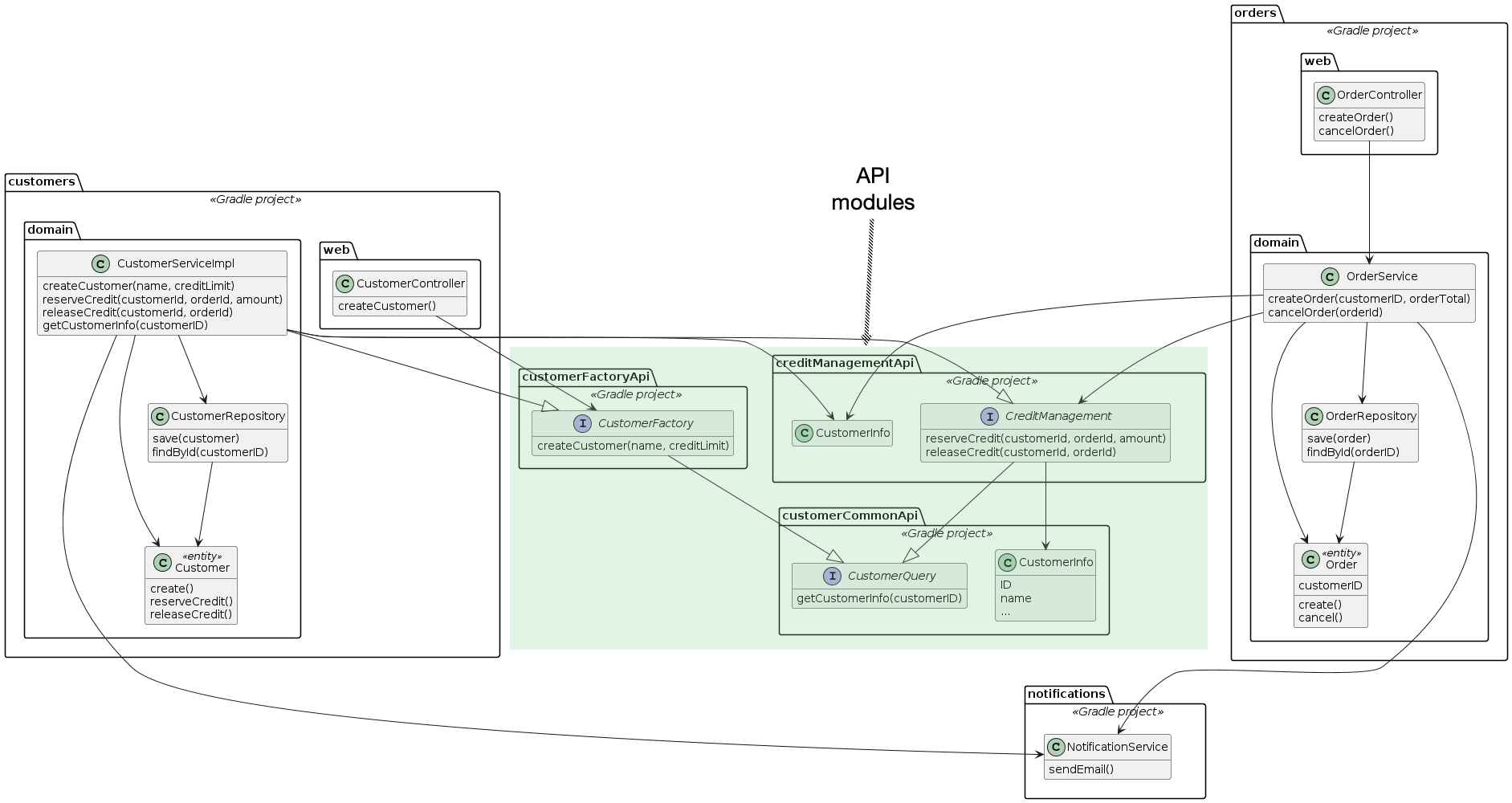

Using domain API modules to reduce build-time coupling

Let’s imagine that the example application consists of a Gradle subproject (or Maven module) for each domain. We can apply analogous physical design principles to a modular monolith to minimize build-time coupling between those domains. One good technique is to split a domain into an API module (i.e. Gradle subproject) and an implementation module. A domain’s clients depend on the API module, which hopefully rarely changes, and not on the implementation module, which changes more frequently. As a result, changes to the implementation module will not trigger unnecessary rebuilds and retests of the domain’s clients.

For example, in the example application the customers domain would have a customers-api Gradle project and a customers (implementation) Gradle project.

The customers-api module is a dependency of both the customers module and the orders module.

The customers-api project contains the CustomerService, which is implemented by the CustomerServiceImpl class in the customers project.

Here’s the interface:

public interface CustomerService {

CustomerInfo createCustomer(String name, Money creditLimit);

void reserveCredit(long customerId, long orderId, Money orderTotal);

void releaseCredit(long customerId, long orderId);

CustomerInfo getCustomerInfo(long customerId);

}

This interface contains the methods that are used by other domains, such as orders, as well as the createCustomer() method, which is called by the CustomerController.

The CustomerService interface is, for example, injected into the OrderService:

public class OrderService {

public OrderService(CustomerService customerService, ...) {...}

...

The customers-api project also contains the CustomerInfo DTO.

The orders module no longer build-time coupled to the customers module and so it will not be rebuilt and retested as a result of changes to the customers module.

Applying the Interface segregation principle (ISP)

One issue with the CustomerService interface, however, is that the createCustomer() method is not used by the orders module.

As a result, there’s still unnecessary build-time coupling between the customers and orders domains.

Let’s imagine, for example, that you need to add an attribute to Customer entity, which in turn adds a new parameter to the CustomerService.createCustomer() method.

Despite not using the createCustomer() method, the orders module will still be rebuilt and retested.

We can further reduce the build-time coupling by applying the Interface segregation principle.

The Interface segregation principle states that no client should be forced to depend on methods it does not use.

The solution is to split the CustomerService interface into two interfaces: CustomerFactory and CreditManagement, each of which is in a separate API module.

There’s a third API module that these two modules depend on.

The customer-factory-api module contains the CustomerFactory interface:

public interface CustomerFactory {

CustomerInfo createCustomer(String name, Money creditLimit);

}

The CustomerFactory interface is used by the customers web module.

The credit-management-api module contains the CreditManagement interface:

public interface CreditManagement {

void reserveCredit(long customerId, long orderId, Money orderTotal);

void releaseCredit(long customerId, long orderId);

CustomerInfo getCustomerInfo(long customerId);

}

The orders domain depends on this module and uses the CreditManagement interface:

public class OrderService {

public OrderService(CreditManagement creditManagement, ...) {...}

public Order createOrder(long customerId, Money orderTotal) {

...

creditManagement.reserveCredit(customerId, order.getId(), orderTotal);

...

Although this design is more complicated, it reduces the build-time coupling between the customers and orders domains.

The two APIs - CustomerFactory and CreditManagement - can evolve independently without triggering unnecessary rebuilds and retests of each other’s clients.

Summary

Using API (Gradle) modules can reduce build-time coupling between modules since changes to an implementation module will only require that module to be rebuilt and retested. Also, using the Interface Segregation principle and defining multiple API modules can further reduce build-time coupling. Only a subset of a module’s clients might be affected by a change to the module’s API.

Need help with your architecture?

I’m available. I provide consulting and workshops.

Premium content now available for paid subscribers at

Premium content now available for paid subscribers at